“This just in: Apparently, there is more than one

connection between all of the previous rampage killers in the US. Not only did

they all play violent video games at some point, they all watched TV news AND

had access to guns.”

While the above discussion is obviously fake, according to

footage in the Colbert

Report of September 18, 2013 one TV journalist has suggested that we

could perhaps prevent future firearm violence by keeping a register of video

game purchases.

|

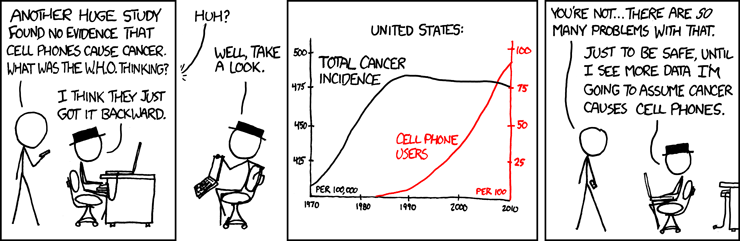

| xkcd on reverse causation |

How did the discussion of what is behind these

horrible shooting rampages end up being about video games? Simple:

As a society, we

want to understand what caused this so we can prevent it in the

future.

As another

video game researcher puts it,

“We don't have a lot of control over many of the factors

that can contribute to violent behavior. But we have some control over violent

video games. We can make it more difficult to get access to them. We can

strengthen our laws against teens acquiring these games.”

Hold the phone; is he talking about video games or

guns? Let’s rewind and make a substitution:

“We don't have a lot of control over many of the factors

that can contribute to violent behavior. But we have some control over guns. We

can make it more difficult to get access to them. We can strengthen our laws

against teens acquiring these guns.”

Everyone knows that you can’t have firearm violence without

firearms. The cool thing about public health is that

- there

is (ideally) a scientific approach to understanding the processes that

lead to outcomes, and

- there

is also (ideally) an approach to deciding what is important to study and

regulate. One of the key questions to ask about a potential research

subject is: how much of an effect would being able to change

this potential cause have on my outcome of interest?

So, keeping in mind the important limitations of

public health research I discussed in my earlier posts, let’s talk about just a

couple of the reasons why keeping video games on the research and policy agenda

is a waste of time and resources:

1. Guns are clearly

responsible for firearm violence and can be regulated, even in other countries

that have traditionally refused limitations. (Take a look at the Emmy Award winning

segment of The Daily Show, where comedian John Oliver discusses the

complete absence of shooting rampages in Australia after gun control with

former Australian prime minister John Howard.)

2. Scientists have

been studying the effects of video games for decades, and there is still no

consistent relationship between violent video games and real-world violent

acts. In fact, one recent

well-controlled study showed no long-term ties between violent video

games (when measured by themselves) and real-world seriously violent acts when

other factors like substance use or living in a violent community are taken

into account (p.932; remember the previous discussion about statistical levels

and coincidence). It did show, however, that visiting websites that “feature

real people fighting, shooting or killing” is associated with real-world

violent acts. I’ll get back to more of the methodological problems in future

blog posts, but feel free to read anything by Chris

Ferguson or Craig

Anderson for more information and contrasting views on the research to

date.

3. Video games and

other media exposures are not proximal causes,

only distal links on a chain of other causes (see an excellent article by Krieger for

a thorough discussion). And contrary to the implication above, we

actually do have some control over the more proximal causes

(e.g, guns).

4. Multifinality and equifinality.

These limitations lead to different ways of viewing how likely or probable

something is (risk). And this little bit is going to be our public health

lesson for the day.

Multifinality: People can have the same risk

factors (potential causes of a bad event) but different outcomes.

Aaron Alexis and Adam Lanza both played video games (like

the majority

of people in the US). They also (probably) watched TV, were male, and

walked upright.

The above helps us understand questions about risk that are

vital to approaching things from a public health perspective. For the terms

below, I paraphrase a discussion by Swanson,

substituting “violent video games” for “mentally ill”.

Absolute risk: The vast majority of people who

play violent video games are not violent.

Relative risk: People who play violent video

games are no more likely to commit violent crimes than those who do not play

violent video games. (However, people who have access to guns are more

likely to shoot people.)

And then there’s equifinality: A variety

of risk factors can lead to the same outcome.

Aaron

Alexis was a former Naval reservist with a criminal history of

violence and current money troubles. He was also an African-American practicing

Buddhist who had sought help from the Veterans Administration for paranoia and

hearing voices. He had a legally-purchased

shotgun.

Adam Lanza was a well-off young white man who lived an

isolated life after years of being bullied in

high school. He also had access to a stockpile

of guns with over 1600 rounds of ammunition.

Attributable risk: Violence is a societal

problem caused largely by things other than violent video games (ready

availability of guns, for example).

The stories we hear about rampages are just that, stories.

They may serve the purpose of trying to make sense of something horrible, but

it’s time to move on from investing more time and money into studying video

games and consider what could provide “more bang for the

buck”. Some of the key assumptions of the Code

of Ethics for Public Health say that a base for action should improve

health through seeking and acting on knowledge, and that there is a moral

obligation to share what is known.

Yes, there are barriers to getting the knowledge out there

(e.g., publication bias, selective outcomes reporting). Yes, it is hard to take

action on things that we know (e.g., gun

control politics). But given that toddlers

with guns seem to have killed more Americans this year here in the US

than terrorists did, it’s time to take advantage of this window of opportunity

and enact real change in the clearest cause of firearm violence—access to guns.

reprinted from mcoldercarras.com, 9/2013

reprinted from mcoldercarras.com, 9/2013